Legislation, Policies, Value and Quantity

Talbot Botanic Gardens, Malahide Demesne

2.1 European Union Legislation

Currently at EU level there are no directives relating specifically to the planning, design and management of parks and open spaces.

The ‘European Landscape Convention’ (also known as the ‘Florence Charter’), was adopted in March 2004. This is the first international treaty to be exclusively devoted to all aspects of the European landscape. It applies to the entire territory of the member countries and covers natural, rural, urban and peri-urban areas. It concerns landscapes that might be considered outstanding as well as every day or degraded landscapes. The focus of the charter is the protection, management and planning of all landscapes and the raising of awareness of the value of a living landscape

Ireland ratified the ‘European Landscape Convention’ (ELC) in 2004. The Convention defines landscape as:

|

“... an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors.” and “as a zone or area as perceived by local people or visitors, whose visual features and

character are the result of the action of natural and/or cultural (that is, human) factors.”

|

The Department of Environment, Community and Local Government has produced a recently adopted ‘National Landscape Strategy’ (NLS), in order to meet its obligation under the Convention.

EU Green Infrastructure Strategy

In 2013, the European Commission adopted a Green Infrastructure Strategy, Green Infrastructure (GI) — Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital “to promote the deployment of green infrastructure in the EU in urban and rural areas.”

The strategy recognises that Human society depends on the benefits provided by nature such as food, materials, clean water, clean air, climate regulation, flood prevention, pollination and recreation. However, many of these benefits, frequently referred to as ecosystem services, are used as if their supply is almost unlimited and treated as free commodities whose true value is not fully appreciated. The strategy further recognises that the Green Infrastructure approach is a successfully tested tool for providing ecological, economic and social benefits through natural solutions. It helps us to understand the value of the benefits that nature provides to human society and to mobilise investments to sustain and enhance them.

The Fingal Open Space Strategy has been prepared in line with this approach.

Royal Canal Walkway, Ashtown

2.2 National Legislation and Policies

Historical Background

The provision of open space has historically been the remit of the local authority. The original legislation relating to the provision of open space was the Town and Regional Planning Act, 1934. This Act stated that provision may be made by Planning Schemes for the reservation of particular lands for the use as public parks, recreation grounds, open spaces, allotments, or other particular purposes, whether public or private.

In 1963 the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act was passed.

This act repealed the earlier Town Planning Acts and placed an obligation on local authorities to make Development Plans. The Act stated that a development plan shall consist of a written statement and a plan indicating the development objectives for the area in question, including objectives for preserving, improving and extending amenities.

In 1987 the Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government published the document (DoEHLG) published: ‘A Policy for the Provision and Maintenance of Parks, Open Spaces and Outdoor Recreation Areas by Local Authorities’. This guidance which is now almost 30 years old still represents the only national advice specifically for local authorities providing for parks, open spaces and outdoor recreational activities. This document identified the growing demand for the provision of public parks, open spaces and recreational areas and the need to co-ordinate this provision if public demand is to be adequately catered for and if maximum value is to be obtained from the limited resources available. At that time, emphasis was placed on providing a hierarchy of spaces with prescriptive quantitative guidance standards as follows:

Local Park of minimum 2 hectares open space per 1,000 population with a typical provision of a 16 Hectare, Neighbourhood Park and 2 No. 2 Hectare. Local Parks per 10,000 population.

The Neighbourhood Park should be capable of including:

• Up to 6 football pitches

• Up to 10 tennis courts

• Up to 2 netball or basketball courts

• Up to 2 golf putting greens

• 1 children’s playlot

• 1 athletic facility

• Car parking

More recently, emphasis has been re-balanced to focus on the quality and accessibility of provision. In this respect, the most the most influential documents are the U.K. Fields in Trust’s document, ‘Planning and Design for Outdoor Sport and Play’. In 2009; the Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government published the document “Guidelines for Planning Authorities on Sustainable Residential Development in Urban Areas (Cities, Towns & Villages)”.

Current Legislation & Guidance

The Planning and Development Act 2000, as amended, sets out principles for the control of private land in the interests of the common good and for proper planning and sustainable development. Section 10 of Part II of the Act sets out the requirements for each county development plan including the provision for zoning of land for recreation and open space. The Act also requires Development Plans to set out objectives for the preservation, improvement and extension of amenities and recreational amenities.

‘Sustainable Residential Development in Urban Areas, Guidelines for Planning Authorities

The ‘Sustainable Residential Development in Urban Areas, Guidelines for Planning Authorities’, published in 2009 state that the provision of appropriately designed open space is a key element in defining the quality of the residential environment. This document highlights the importance of strategic city or county-wide policies for open space and recreational facilities (both indoor and outdoor), which are based on an assessment of existing resources and user needs, including local play policies for children. Area-wide green space strategies facilitate not only the development of a hierarchy of provision – ranging from sub regional parks down to pocket parks – but also the creation of links or green corridors between parks, river valleys and other amenity spaces. Such strategies should be supported by an audit of existing green spaces within the area.

Sustainable Residential Development Guidelines recommend qualitative standards, these including:

- Design: The layout and facilities – particularly in larger parks – should be designed to meet a range of user needs, including both active and passive recreation, as identified in the city/county strategy referred to above.

- Accessibility: Local parks should be located to be within not more than 10 minutes’ walk of the majority of homes in the area; district parks should be on public transport routes as well as pedestrian/ cycle paths. Playgrounds should be carefully sited within residential areas so that they are both easily accessible and overlooked by dwellings, while not causing a nuisance to nearby residents.

- Variety: A range of open space types should be considered having regard to existing facilities in the area and the functions the new spaces are intended to provide.

- Shared use: The potential for maximising the use of open space facilities (such as all-weather pitches) should be explored, for example, by sharing them with nearby schools.

- Biodiversity: Public open spaces, especially larger ones, should provide for a range of natural habitats and can facilitate the preservation of flora and fauna. Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems are often used to reduce the impact of urban runoff on the aquatic environment.

|

Ardgillan Demense, Skerries

- Provision for allotments and community gardens: Allotments are small plots of land which are let (usually by a local authority) to individuals for the cultivation of vegetables and plants. They are of particular value in higher density areas.

|

The recommended quantitative standards are:

- In green-field sites or those sites for which a local area plan is appropriate, public open space should be provided at a minimum rate of 15% of the total site area. This allocation should be in the form of useful open spaces within residential developments and, where appropriate, larger neighbourhood parks to serve the wider community;

- In other cases, such as large infill sites or brown field sites public open space should generally be provided at a minimum rate of 10% of the total site area; and

- In the case of institutional lands and some private sites characterised by substantial open lands which in some cases are accessible to the wider community, any proposals for higher density residential development must take into account the objective of retaining the “open character” of these lands, while at the same time ensuring that an efficient use is made of the land. In these cases, a minimum requirement of 20% of site area should be specified; however, this should be assessed in the context of the quality and provision of existing or proposed open space in the wider area

|

Regarding the quantitative aspect, the Guidelines note it will be necessary to take a more flexible approach to quantitative open space standards and put greater emphasis on the qualitative standards.

The National Landscape Strategy

The Irish government recently adopted a National Landscape Strategy. This aims to: implement the European Landscape Convention in Ireland by providing for specific measures to promote the protection, management and planning of the landscape. The National Landscape Strategy sets out a

series of actions the following of which are relevant to and supported by theFingal Open Space Strategy:

-

Action 8 Develop public awareness programmes to (i) promote an understanding of the nature of landscape, its value as a cultural and visual resource, its role in promoting Ireland’s attractiveness as a tourist destination, and also in ensuring economic prosperity and(ii) how it should be managed sustainably and beneficially to meet the challenges of climate change adaptation and mitigation, food-security, health and well-being.

-

Action 9 Provide appropriate support to public participation initiatives to ensure that landscape change management is effective and evidence based and informed by best practice.

-

Action 16 Develop methods of participation for organisations, public and private, as well as individuals in the shaping, reviewing and monitoring of landscape policies and objectives and, if necessary, establish new innovative approaches. This includes fostering actions to achieve delivery of these to encourage citizens, as well as the State, in the sustainable management of the landscape.

|

Baldoyle Racecourse Park Community Garden

2.3 Play Policy

International Play Policy

Ireland ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992. Article 31 of the convention recognises the right of the child to “engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.”

The Policy Context for this objective recognised that play, recreation and cultural activities are essential childhood experiences which enrich the lives of children and provide them with experiences and competencies that will serve them well in later life. It further recognised that the importance of play and recreation in children’s lives is reflected in Article 31 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The National Play Policy was launched in March 2004 by the Department of Children and Youth Affairs and titled Ready, ‘Steady, Play! A National Play Policy’. With the publication of this policy, Ireland became one of the first countries in the world to produce a detailed national policy on play. The reason for the development of such a policy by Government was to honour commitments made in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the National Children’s Strategy (2000) and the Programme for Government (2002).

The definition used in the National Play Policy to provide an understanding of play is:‘Play is freely chosen, personally directed, intrinsically motivated behaviour that actively engages the child.’

Put more simply, it could be said that play is what children do when no- one else is telling them what to do. The vision statement for the policy is as follows: ‘An Ireland where the importance of play is recognised, so that children experience a range of quality play opportunities to enrich their childhood’.

The objectives of the National Play Policy are:

National Play Policy

Beech Park Playground, Clonsilla

- To give children a voice in the design and implementation of play policies and facilities.

- To raise awareness of the importance of play.

- The National Children’s Strategy published in 2000 recognised that all children have a basic range of needs and set out a schedule of objectives to address these needs. Objective D of the strategy stated that “Children will have access to play, sport, recreation and cultural activities to enrich their experience of childhood”.

- To ensure that children’s play needs are met through thedevelopment of a child-friendly environment.

- To maximise the range of public play opportunities available to allchildren, particularly children who are marginalised, disadvantaged or who have a disability.

- To improve the quality and safety of playgrounds and play areas.

- To ensure that the relevant training and qualifications are available to persons offering play and related services to children.

- To develop a partnership approachto funding and developing play opportunities.

- To improve information on, and evaluation of, play provision for children in Ireland.

|

Implementation of the policy

There are 52 actions in the National Play Policy that follow from the objectives outlined above. Responsibility for implementation of these

actions lies with a number of entities including Local Authorities and the implementation of the policy is monitored by the Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA). The play policy references the 1987 Park Policy for Local Authorities, published by Department of the Environment. This document recommended a minimum level of playlot provision at 1 playlot (incorporating fixed play equipment) per 10,000 population. This standard can still be regarded as a National benchmark. In Fingal the standard overall provision is approaching 1 play lot per 5000.

PARKS POLICY FOR LOCAL AUTHORITIES: published by Department of the Environment in 1987

facilities and that these facilities should be provided at a rate of 4 square metres of play area per residential unit. The plan further requires the provision of play facilities for smaller children within 100 metres of all houses in new residential developments. This requires the development of Pocket Parks to accommodate these quite modest facilities. The plan also requires the provision of larger play facilities to suit a wider age group within 400m of all houses in new residential developments.

The Development Plan is currently being reviewed. This policy will be updated to reflect any changes to the open space strategy policy arising from this process

Local Play Policy

In national terms The Council achieves a relatively high standard of play provision. The Fingal Development Plan 2011 – 2017 requires that all new residential schemes in excess of 50 units should incorporate playground facilities and that these facilities should be provided at a rate of 4 square metres of play area per residential unit. The plan further requires the provision of play facilities for smaller children within 100 metres of all houses in new residential developments. This requires the development of Pocket Parks to accommodate these quite modest facilities. The plan also requires the provision of larger play facilities to suit a wider age group within 400m of all houses in new residential developments. The Development Plan is currently being reviewed. This policy will be updated to reflect any changes to the open space strategy policy arising from this process

Natural Play

Climbing trees, playing in streams, running through meadows are activities most people tend to associate with their childhood. Nowadays however many children, particularly in urban areas, do not have the same natural

play opportunities . Play opportunities now often come as playgrounds with metal and timber play equipment and safety surfaces. There is an increasing trend around Europe to provide alternative play areas of a more natural character. In Ireland, these natural playgrounds are very uncommon and the Council intends to develop demonstration sites for natural playgrounds in a variety of settings e.g. regional parks, housing estates and pocket parks.

A pilot project showcasing Natural Play has been developed for St. Catherine’s Park in Lucan.

Example of Natural Play Area

2.4 Local Policies

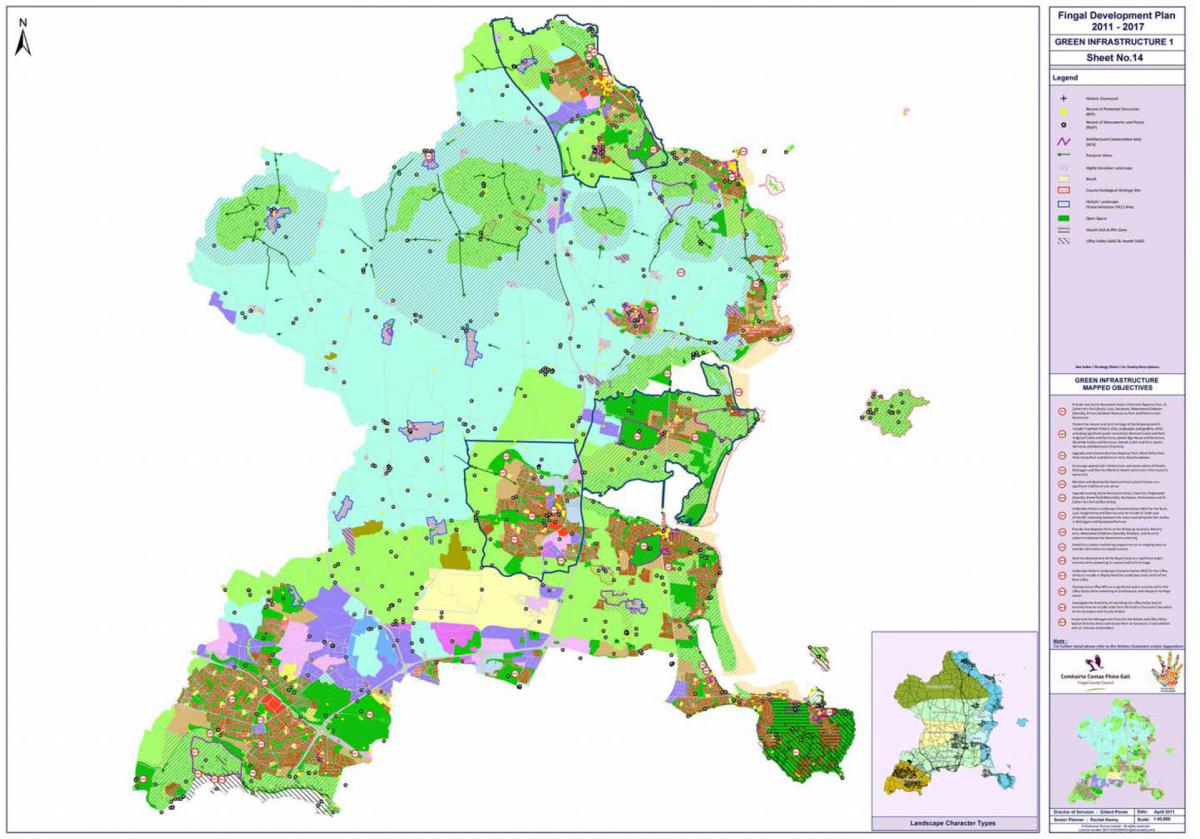

Fingal Development Plan 2011 – 2017

Green Infrastructure

Chapter 3 of the ‘Fingal Development Plan 2011-2017’ contains the following aim in respect of Green Infrastructure:

| “Create an integrated and coherent green infrastructure for the County which will protect and enhance biodiversity, provide for accessible parks and open space, maintain and enhance landscape character including historic landscape character, protect and enhance architectural and archaeological heritage and provide for sustainable water management by requiring the retention of substantial networks of green space in urban, urban fringe and adjacent countryside areas to serve the needs of communities now and in the future including the need to adapt to climate change.” |

Section 3.1 of the Development Plan recognises that, ‘‘High-quality accessible parks, open spaces and greenways provide health benefits for all including space for children to play, a meeting place for people from all backgrounds and communities and can provide for the development of safe and attractive walking and cycling routes.”

Parks, Open Space and Recreation is identified as a key theme which The Council’s Green Infrastructure Policy shall address. Section 3.3 of the Development Plan outlines Green Infrastructure Objectives.

Specific objectives in relation to Parks, Open Space and Recreation are as follows:

|

Objective GI18

Maximise the use and potential of existing parks, open space and recreational provision, both passive and active, by integrating existing facilities with proposals for new development and by seeking to upgrade existing facilities where appropriate.

Objective GI19

Provide a range of accessible new parks, open spaces and recreational facilities accommodating a wide variety of uses (both passive and active), use intensities and interests.

Objective GI20

Consider all sections of the community in the provision of parks, open space and recreational facilities.

Objective GI21

Seek to enhance connectivity for people through the provision of parks, open space and recreational facilities.

Objective GI22

Ensure parks, open space and recreational provision is appropriately designed to respond to and integrate with the landscape and townscape context.

Objective GI23

Ensure that proposals for parks, open space and recreational facilities which may have an impact on the Natura 2000 network either directly or indirectly are subject to Appropriate Assessment and are given very careful consideration.

Objective GI24

Seek to draw public use away from sensitive Natura 2000 sites through the use of alternative provision for parks, open space and recreation, where appropriate.

Objective GI25

Provide attractive and safe routes linking key green space sites, parks and open spaces and other foci such as cultural sites and heritage assets as an integral part of new green infrastructure provision, where appropriate and feasible.

Objective GI26

Ensure all proposed walking and cycle routes in the Liffey Valley are sited and designed to ensure the protection of the Valley’s heritage including its biodiversity and landscapes.

Objective GI27

Provide opportunities for food production through allotments or community gardens in new green infrastructure proposals where appropriate.

|

The Development Plan also states that, “The provision of accessible open space is an integral part of the provision of high-quality green infrastructure for communities and forms a core element in the emerging Green Infrastructure Strategy for the county.”

Green Infrastructure Map 1 from the Development Plan outlines a number of relevant mapped objectives:

|

GM1 Provide new Active Recreational Hubs in Bremore Regional Park, St. Catherine’s Park (Rush), Lusk, Donabate, Mooretown/Oldtown (Swords), Drinan, Baldoyle Racecourse Park and Phoenix Park Racecourse.

GM2 Protect the natural and built heritage of the following (which include important historic sites, landscapes and gardens, while providing significant public amenities): Bremore Castle and Park, Ardgillan Castle and Demesne, Newbridge House and Demesne, Malahide Castle and Demesne, Swords Castle and Park, Santry Demesne and Beechpark (Clonsilla).

GM3 Upgrade and enhance Bremore Regional Park, Ward Valley Park, Tolka Valley Park and Millennium Park, Blanchardstown.

GM5 Upgrade existing Active Recreation Hubs in Skerries, Ridgewood (Swords), Broomfield (Malahide), Hartstown, Porterstown and St. Catherine’s Park (Liffey Valley).

GM8 Provide new Regional Parks at the following locations: Baleally Lane, Mooretown/Oldtown (Swords), Baldoyle, and Dunsink subject to Appropriate Assessment screening.

GM10 Seek the development of the Royal Canal as a significant public amenity while protecting its natural and built heritage.

GM12 Develop Anna Liffey Mills as a significant public amenity within the Liffey Valley while protecting its architectural and industrial heritage values.

|

Recreational Hubs

The Council is seeking to develop active ‘Recreational Hubs’ at various locations throughout Fingal as provided for in the map based objectives above. These hubs will be provided by or facilitated by the Council and will allow clubs from different sporting codes to share facilities such as changing/meeting

rooms, car-parking, all-weather pitches, and other ancillary facilities. The Recreational Hubs concept has been developed to encourage multi-use and sustainable community sporting facilities. The hub will also act as a catalyst to build and bring communities together by delivering services that meet the needs of the community and serve other purposes such as providing a safe meeting place and hosting the delivery of community programmes that develop community capacity and connectivity. Recreational Hubs shall be inclusive and open to all sectors of the community, including sport participants and members at all ability levels and age groups.

The purpose of the hub is to locate sport in an area where it doesn’t conflict with adjoining residential use. It will create intensive recreational areas. The Council will endeavour to locate these hubs adjacent to school buildings or other municipal facilities to increase the use of same.

Bremore Park Recreational Hub, Balbriggan

Development Plan Extract - Green Infrastructure Map 1 15

Principles of Open Space Provision

Section 7.5 of the ‘Fingal Development Plan 2011-2017 outlines five basic principles for the provision of open space which are as follows:

|

Hierarchy

Design open space and recreational facilities on a hierarchical basisaccording to the needs of a defined population and having regard to the emerging Green Infrastructure Strategy.

Accessibility

Ensure as far as practical open space and recreational facilities are accessible by sustainable means of transport namely walking, cycling and public transport, depending on the catchment of the facility in question.

Quantity

Provide sufficient quantities of open space and recreational facilities.

Quality

Meet the needs and expectations of the user through the provision of high quality facilities. Different types of open space and recreational facilities meet different needs and therefore have different functions. Larger open spaces and recreation facilities should perform multiple functions i.e. passive and active recreational use.

Private Open Space

Provide adequate private open spaces such as back gardens, balconies.

Further details in relation to the provision of Public Open Space in Fingal are provided in Part 2 of this document.

|

2.5 Value of Parks and Open Spaces

Introduction

Public open space can have a positive impact on physical and mental well-being as it provides spaces to meet, interact, exercise and relax. It

needs to be appropriately designed, properly located and well maintained to encourage its use and is a key element in defining the quality of the residential environment. It adds to the sense of identity of a neighbourhood, helps create a community spirit, and can improve the image of an area.

Parks and Open Spaces are a shop window for local authorities and well managed and clean outdoor spaces are a source of pride for local communities. The costs of building, maintaining, or upgrading parks are readily calculated and conspicuous but the benefits open space provides are spread over many areas, making them hard to quantify and easy to overlook.

Parks and open spaces are vital contributors to the achievement of wider urban policy objectives, including job opportunities, youth development, public health, and community building. They provide a sense of place and engender civic pride, enabling social interaction and helping to reduce social exclusion particularly in deprived areas.

Public green spaces also help to conserve natural systems, including carbon, water and other natural cycles, supporting ecosystems and providing the contrast of living elements in both designed landscapes and conserved wildlife habitats.

Providing for the recreational and leisure needs of a community assists the economic development of an area, increasing its attractiveness as a place for business investment and for living, working and leisure pursuits.

This section will look at the evidence based empirical research relating to the value of Public Open Space under the following headings:

• Public Health Value

• Community and Sport Value

• Enhanced Property Value

• Ecological / Natural System Value

• Heritage and Tourism Value

Public Health Value

Childhood obesity has become national health concern in recent years. One in five Irish children is considered to be obese with levels of obesity reaching epidemic proportions in recent years, according to a four-year study carried out by the Department of Health.

Balheary Skatepark, Swords

This increase in obesity is linked to ever more sedentary lifestyles and a reduction in outdoor activity. Inactivity breeds inactivity, so a lack of exercise when young can in turn create problems in adulthood. It is not just people’s physical health that is at risk, there are concerns too about people’s mental well-being.

Access to good-quality, well-maintained public open spaces can help improve our physical and mental health by encouraging people to walk more, play sport, or simply enjoy a green and natural environment.

Safe, clean spaces encourage people to take more exercise and therefore offer significant health benefits. Some doctors even prescribe a walk in the park to aid patients’ health. A study of walking groups has shown that just increasing the distance walked from one to two miles a day means one less death per year among 60 male patients aged 61-80 who suffer from heart disease.1

1 Bird, W. (2003) ‘Nature is good for you!’ ECOS, Vol. 24(1) pp29-31.

In a UK study regular walking was shown to reduce the incidence of heart attacks by 50%, diabetes by 50%, colon cancer by 30% and fractures of the femur by 40%. NHS Scotland has calculated that if an additional 1 in 100 inactive people took adequate exercise it would save the health service there £85 Million per annum.

Sports such as soccer and hockey are part of the weekly routine for many people and require good-quality pitches. As people get older, the types of sports they enjoy may change, with activities such as bowls associated with older people. Many of our hard urban public spaces also offer opportunities for less formal but equally beneficial sports, such as skateboarding. All these activities help us to keep fit by protecting the cardiovascular system and preventing the onset of other health problems.

Recent studies have established that the presence of trees and “nearby nature” in human communities generates numerous psychosocial benefits. A series of school-related studies show that children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) show fewer symptoms and girls show more self-discipline in academics if they have access to natural settings. Other studies confirm that hospital patients recover more quickly and require fewer pain-killing medications when having a view of nature. Finally, studies suggest that office workers with a view of nature are more productive, report fewer illnesses, and have higher job satisfaction. In conclusion the Council will continue to take account of the increasing evidence of health related benefits of open space.

Community Value of Open Space

Parks and Open Spaces help build and strengthen ties within communities by bringing people together, including those who may otherwise be separated by ethnic or social background. Public open spaces are open to all and, when properly designed and cared for can provide meeting places and foster social ties. These open spaces shape the cultural identity of an area, are part of its unique character and provide a sense of place for local communities.

Open spaces are not just empty voids. Typically, they are filled with both soft and hard landscape elements to help shape their character and the open spaces near our homes create a valuable place to socialise. In this regard, quality counts; the better the design of the space, the better the quality of the social experience. Research has shown that big, bland spaces on housing estates fail to offer the same opportunities for social cohesion as more personal spaces.2

A key benefit of high-quality public space is its potential as a venue for social events. Well managed events can have a very positive effect on the urban environment, drawing the community together and bringing financial, social and environmental benefits. For example, in the Fingal area, the ‘Flavours of Fingal Festival’ at Newbridge Demesne, the ‘Howth Dublin Bay Prawn Festival’ and ‘Theatre in the Park’ events make use of parks and open spaces as venues. To encourage and support events like these, it is essential to plan the physical layout of public spaces with festivals and other social activities in mind.

Flavours of Fingal, Newbridge Demesne

There is evidence to show that people use their public open spaces more, and are more satisfied with them, if these spaces include natural elements. A view of trees is, along with the availability of natural areas, the strongest factor affecting people’s satisfaction with their local area. It is shown that if green spaces are surrounded by or adjacent to housing, a sense of ownership develops among residents. These areas are less likely to suffer from the kind of problems that arise when there is a lack of perceived ownership. Large, featureless open spaces do not often generate such positive community feelings. It is most beneficial, therefore, to provide smaller green areas close to housing.

2 Quayle, M. and Dreissen van der Lieck, T. C. (1997) ‘Growing community: a case for hybrid 18

landscapes’. Landscape and Urban Planning, 39, pp99-107

Enhanced Property Value

A high-quality public environment can have a significant positive impact on the economic life of an area and is therefore an essential part of any successful town or city. As towns and cities increasingly compete with one another to attract investment, the presence of good quality open spaces becomes a vital element of any economic strategy.

A good public landscape also offers very clear benefits to the local economy in terms of stimulating increased house prices, since house-buyers are willing to pay to be near green space. For example, it has been shown that a view of a park or having a park in close proximity to housing can increase property prices.

For commercial enterprises, a good-quality public environment can attract more people into an area. It has been shown, for example, that well-planned improvements to public spaces within town centres can boost commercial trading significantly and generate significant private sector investment.

Ecological and Natural System Value

Open space possesses ‘natural system value’ when it provides direct benefits to human society through such processes as ground water storage, carbon sequestration climate moderation, flood control, storm damage prevention, and air and water pollution abatement. It is possible to assign a monetary value to such benefits by calculating the cost of the damages that would result if the benefits were not provided, or if public expenditures were required to build infrastructure to replace the functions of the natural systems. Our parks and open spaces also provide important habitats for many species of flora and fauna such as otters, kingfishers and bats which are protected under European and Irish legislation.

In Melbourne, Australia the planting of 100,000 trees has led to a Carbon reduction equivalent to 1.3 Million tonnes with a consequent annual saving of AU$29 Million.

Another example of Natural System Value is the Charles River Basin in Massachusetts, where 8,5000 acres of wetlands were acquired and preserved as a natural valley storage area for flood control for a cost of $10 million. An alternative proposal to construct dams and levees to accomplish the same goal would have cost $100 million. In another study, the Minnesota

Department of Natural Resources calculated that the cost of replacing the natural flood water storage function of wetlands would be $300 per acre- foot of water.

Details of how Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) can be appropriately incorporated into Public Open Spaces are included in Part 3 of the document.

Trees are an essential part of a healthy urban environment; their root systems hold soil in place, preventing erosion. Trees help maintain healthy air quality by absorbing, or sequestering, carbon dioxide and converting it into oxygen to breathe. One acre of trees provides enough oxygen for 18 people, and absorbs as much carbon dioxide as a car produces in 26,000 miles. Trees also remove sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxide, two major components of acid rain and ozone pollution, from the air. Trees reduce noise pollution by acting as a buffer and absorbing urban noise. Trees also create homes for birds and other wildlife.

In providing Open Space the Council recognises the significant Ecological and Natural Systems benefits generated by it.

Wildflower Meadow, St. Catherine’s Park, Lucan

Heritage and Tourism Value

Tourism is an important source of revenue, investment and employment throughout Ireland. Within Fingal, alongside our coastline and countryside, the Council’s heritage properties are a unique selling point for the County and must be managed correctly and in a sustainable manner to ensure their

success and longevity.

Tourism has been identified as one of the main areas for economic growth and development in Fingal. The ‘Fingal Heritage Plan’ recognises the significant opportunity represented by heritage properties as tourism assets conferring important economic benefits on the county. It is recognised that tourism can have negative impacts on areas such as natural resources, pollution, consumption patterns and the environment. However, when heritage tourism development is appropriately implemented, it also helps to protect our natural and cultural treasures and improve the quality of life for residents and visitors alike. In order for the tourism industry to survive, it is important that responsible and sustainable planning and management techniques are applied.

The Fingal Tourism Strategy notes that the tourism and hospitality sector plays a critical role in the health of Fingal’s economy as well as enhancing the quality of life for its residents. The future success of tourism depends on a shared vision guiding an integrated response from a wide range of stakeholders including local government, businesses, community groups and individuals. Based on its natural and man-made assets, Fingal has the potential to project a number of key appeals and attractors to well defined segments of the visitor markets. The vision for the future is one of a fresh start in maximising the potential to deliver distinctive visitor experiences while enhancing the quality of life for the area’s residents and sustaining the natural environment.

Heritage properties in Fingal represent a key element of Sustainable Tourism. Several of our large regional parks are also heritage properties and function to manage and conserve parts of the county’s natural and built heritage. Over 40% of the 2,000 hectares managed as parks and open spaces in Fingal can be regarded as important historic landscapes. It is therefore essential to understand and appreciate these properties and landscapes and to promote and present them properly to visitors.

At a national and local level Parks and Gardens play a major role in the tourism economy and are important factors for choosing Ireland as a holiday destination. During 2013 there were over 1.59 million visits by overseas tourists to gardens in Ireland generating an estimated revenue of

€3.4 Billion. Fingal is well placed to take advantage of this trend in heritage tourism.

Conclusion

The foregoing demonstrates the wide range of benefits and value conferred by parks and open spaces and underlines the importance of having a strategy for the development and management of these resources. The Council recognises the health, social, economic and environmental benefits of open spaces. The Council will promote healthy active life styles and encourage a greater use of open space

Newbridge Demesne, Donabate

The Council recognises the health, social, economic and environmental benefits of open spaces. The Council will promote healthy active life styles and encourage a greater use of open space

2.6 Quantitative Aspects Open Space Provision in Fingal

The purpose of this section is to outline the quantity and typology of public open space provision in Fingal. A series of maps are provided at the end of this document which illustrate the distribution of open space in each of our main towns and villages. Separate maps illustrating our major regional parks are also included.

Supply of Open Space in Fingal

In Fingal, land has become public open space through three main processes:

• Open space acquired by the Council

• Dedicated public open space (land generated through the planning

process)

• Land transferred to the Council by Manager’s Order (lands formerly

within the Dublin City Council administrative area).

Open Space Acquired by the Council

Many of our larger Regional Parks and Heritage Properties have been purchased directly by the Council for use as recreational open space. If the property was acquired subject to any trusts, then the local authority

is bound specifically by the trusts set out in the deeds. It should be noted that Section 211 of the Planning and Development Act 2000 provides that any land acquired by a local authority may be sold, leased or exchanged subject to such conditions as the authority considers necessary. Open space may also become available following the closure and reclamation of former landfill sites. Examples of this approach in Fingal are the major new parks are being developed at Dunsink in Dublin 15 and at Baleally near Lusk.

Dedicated Public Open Space

This refers to lands conditioned as public open space by planning permission and legally dedicated to the Council. The lands are held on behalf of or in trust for the public. The Council is legally prevented from disposing of these

lands or using them for purposes other than recreational open space. While The foregoing demonstrates the wide range of benefits and value conferred by parks and open spaces and underlines the importance of having a strategy for the development and management of these resources.

title for this land passes to the Council, there can be no disposal of the land by the Council. Under current arrangements, the Council cannot give any title for this land whether by way of lease, transfer or licence to any person or group. This can lead to restrictions in relation to third party use and management of this land.

Lands Transferred to the Council by Manager’s Order

The Council also has public open space, mainly in Sutton, Baldoyle and Howth, which was originally taken in charge by Dublin Corporation (now Dublin City Council) under Manager’s Order. Title to these lands remains with the original landowner but so long as it is used as public open space as detailed in the original Manager’s Order public access to the land for recreational use will remain unfettered.

Quantity of Open Space

The Council has approximately 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) of public open space, sixty per cent of which has been generated through the planning process. The quantitative standard used through the planning process requires that 25 hectares is provided per 10,000 of population. This is

derived from a long established standard of British origin known as the ‘6 Acre Standard’ which provides for 6 acres per 1,000 population. This standard was proposed by the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA) of the UK in the 1930’s and has become the norm for quantitative provision of open space and is the standard used in Fingal.

While the approach of the current Development Plan has moved from a quantitative to a qualitative emphasis, there are still objectives relating to the amount of open space a particular development will generate. Objective OS02 states that the minimum public open space required is 2.5 hectares per 1000 population of which 10% must be provided on site. The Council has the discretion to accept a financial contribution for the remaining area. This contribution will then be made available for the provision of public open space.

Currently we have a very extensive public provision of grass sports pitches in Fingal. These pitches are allocated to local clubs on an annual basis. The Council maintains almost 170 grass sports pitches for public use. This services the needs of 76 sports clubs and during the current year the number of teams in these clubs playing on our pitches reached 936 (107 adult and 829 juvenile teams.)

Hierarchy of Open Space

Public Open Space has been described in two ways in successive County Development Plans and both sets of terms are in use.

These are:

- Class 1 & Class 2 which focuses on a quantitative provision system and

- A qualitative and accessibility provision system.

|

Open Space Classification

Open Space ‘Class 1’ and ‘Class 2’ have traditionally been used to describe open space to be provided through the planning process and these terms still form the basis of quantitative assessment of open space provision. Class 1 open space is normally constituted as a significant local park which provides inter alia for active recreation in the form of playing fields. Class 2 public open spaces are generally smaller and more numerous and are located in and around residential areas. They provide opportunities for informal recreation and play.

A significant amount of open space in Fingal is present in the form of roadside verges in urban and residential areas which provide for sight-lines, future road-widening and other non-recreational purposes. This open space is outside the scope of the traditional classification system outlined above. The manner in which this land is managed has important implications for the resourcing of open space maintenance and this issue is addressed comprehensively in Part 3 of this document.

St Catherine’s Park, Lucan

Accessibility of Open Space

The ‘Fingal Development Plan 2011 – 2017’ changes the emphasis from a quantitative approach to one which focuses on accessibility. The standards allow the provision of a wide variety of accessible public open spaces to meet the diverse needs of the county’s residents. The provision of pocket parks and more local, urban parks has been emphasised to achieve a more accessible arrangement. The table below taken from the ‘Fingal Development Plan 2011-2017’ outlines the open spaces hierarchy and accessibility standards which apply.

Extract from Fingal Development Plan 2011 - 2017